Russia’s invasion of its neighbor will likely have a protracted impact on commodities, affecting oil and gas prices more severely this year and food prices well into next year.

Four main factors shape our outlook:

• The war aggravated already surging commodity prices. Energy and food helped boost inflation last year, with oil and gas supplies tight after years of subdued investment and geopolitical uncertainty. This was a main inflation driver in Europe and, to a lesser extent, the United States. Rising food prices also played a major role in most emerging market and developing economies, as extreme weather reduced harvests and mounting oil and gas prices drove up fertilizer costs.

• Demand surged last year amid policy support, while supply bottlenecks grew on factory closures, port restrictions, shipping congestion, container shortages and worker absences. Inflation rose as a result, especially where recoveries were strongest. Demand should soften this year as policy support is withdrawn and supply bottlenecks ease, but China’s recurrent lockdowns, war in Ukraine, and sanctions on Russia will likely prolong disruptions in some sectors into next year.

• Demand is also rebalancing from goods to services. Spending shifted toward goods as pandemic restrictions disrupted in-person activities, with supply bottlenecks helping to boost goods prices. Though service inflation started picking up last year, pre-crisis spending patterns haven’t fully returned and goods inflation remains prominent in most countries. Services demand will increase further as the pandemic eases, and overall inflation should return to where it was before the coronavirus.

• Labor supply remains limited after significant tightening in some advanced economies like the United States and United Kingdom. Worker shortages, mainly in contact-intensive industries, are lifting wages, though inflation has eroded pay gains. Meanwhile, the pandemic reduced labor-force participation in advanced economies. These shifts appear related to earlier retirements and workers being unwilling or unable to return as infections continue. Some workers are putting in fewer hours. We assume labor supply will gradually improve this year as the health crisis abates, but the effects will be moderate and unlikely to significantly ease upward wage pressure.

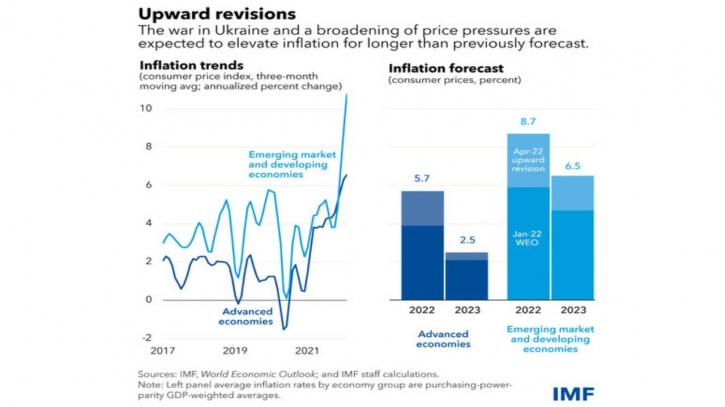

Under these conditions, we expect already-elevated inflation to persist for longer. Our projections call for the pace in advanced economies to reach a 38-year high of 5.7 percent, while price increases in emerging market and developing economies will accelerate to 8.7 percent, the fastest clip since the global financial crisis in 2008. Those rates would then cool next year to 2.5 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively.

Importantly, surging prices will have the greatest effects on vulnerable populations, particularly in low-income countries. High overall inflation will also complicate the trade-offs for central banks between containing price pressures and safeguarding growth.

While our baseline expectation is that inflation will eventually ease, inflation could turn out higher for several reasons. Worsening supply-demand imbalances, including from the war, and further commodity-price gains could keep the pace of inflation persistently high. Moreover, both the war and renewed pandemic flare-ups could prolong supply disruptions, further increasing costs of intermediate inputs. In a context of tight labor markets, nominal wage growth could also accelerate to catch up with consumer-price inflation as workers seek higher wages to preserve their purchasing power. This would further intensify and broaden inflation pressures, with the risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations.

Source: Hellenic Shipping News