Sharpie maker Newell Brands Inc. is opening distribution centers in Pennsylvania and North Carolina to lessen dependence on seaports in California. Abercrombie & Fitch Co. is moving more merchandise through New York and New Jersey to avoid West Coast bottlenecks. Air-conditioning manufacturer Trane Technologies PLC is sending most of its cargo this year through ports in the South, instead of the Los Angeles area.

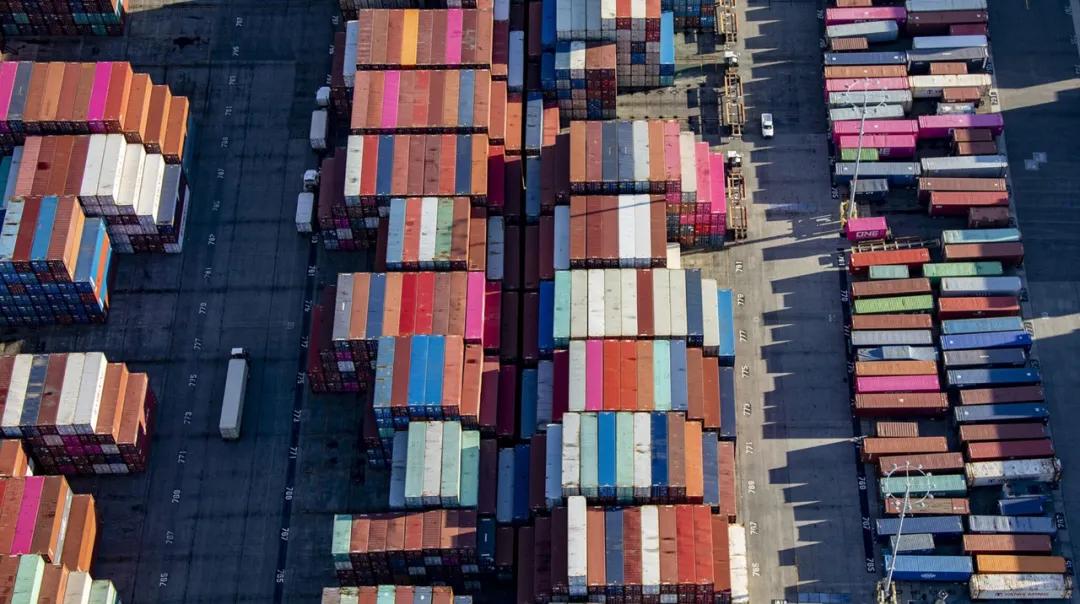

The hierarchy of U.S. ports is getting shaken up. Companies across many industries are rethinking how and where they ship goods after years of relying heavily on the western U.S. as an entry point, betting that ports in the East and the South can save them time and money while reducing risk.

Their reasons range from fears of a dockworkers strike along the West Coast and a repeat of the bottlenecks that roiled supply chains early in the pandemic to a reduced dependence on Chinese production and the need to get products to all parts of the country faster.

In August, Los Angeles lost its title as busiest port in the nation to the Port of New York and New Jersey as measured by the number of imported containers. It trailed its East Coast rival again in that measure during September and October, according to the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association and ports data.

The share of all U.S. containerized cargo handled by Los Angeles and a neighboring port in Long Beach fell through the first 10 months of the year to a combined 25% as measured by weight, according to census data analyzed by Jason Miller, interim chair of Michigan State University’s supply chain management department. That was their lowest level in nearly two decades, down from a height of 33%.

Other ports benefiting from this shift include Savannah, Ga., Houston and Charleston, S.C. All handled more import containers this year through September than during the same period in 2021, according to the PMSA. Railroads and logistics companies are following with new warehouses and services in the Southeast that will make it easier for goods to move from place to place once they arrive by boat.

“People are spreading out their supply chains,” said Craig Grossgart, senior vice president of global ocean for Seko Logistics, an Itasca, Ill.-based freight forwarder that helps companies move goods across the world. ”There are so many customers that got so screwed because they were entirely reliant on L.A. and Long Beach.”

The logistical challenges of spreading imports along the East Coast and the Gulf Coast are massive. Companies hope it will protect them against the costs of any future delays in California, long the preferred gateway for goods from China, but ocean voyages through the Panama Canal and up the Atlantic Coast are longer and more expensive.

Some companies are willing to pay more for the complexity of shipping to multiple ports so their supply chain becomes more flexible, said Sidney Brown, co-owner and chief executive of logistics and trucking provider NFI Industries Inc., which stores and distributes goods for companies.

”Price counts, but risk mitigation is also part of the equation in a much greater way than it was before,” he said.

Any changes in the flow of trade are important for the ports and cities involved. The Port of Los Angeles generates 1.1 million jobs for California, while the Port of Long Beach supports more than 316,000 Southern California jobs, according to PMSA. The Port of New York and New Jersey supported 506,000 jobs as of 2019, according to the Shipping Association of New York and New Jersey.

The West Coast should regain some of its lost trade if members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union—who have been working without a contract since July 1—agree to a new pact with ocean shipping companies and the private firms that run cargo-handling operations from California to Washington state. But some companies may decide it is too risky to return or that it makes sense to have more options throughout the country.

Gene Seroka, executive director of the Port of Los Angeles, said he lost about 21% of cargo volumes from August through November and he expects that about 5% of cargo could be lost for good.

“We’re gonna have to fight to get every piece of it back,” he said.

The shift in trade to the East Coast marks a return to where container ships originated. That industry began in 1956 when the Ideal X, a converted oil tanker, set sail from Newark, N.J., carrying 58 boxes bound for Houston. The boxes made it easy to transport goods by land and then stack the containers onto ships for their journey.

The new transportation system lowered the costs of moving goods from one part of the globe to the other, setting the stage for a boom in worldwide trade. Once China emerged as a dominant exporter of cheaply made goods for giant American retailers such as Walmart Inc., California became an ideal entry point into the U.S. because of its proximity to that part of the world. From there it could be moved by rail and road across the country.

By 2003, West Coast ports from Seattle to San Diego were handling roughly 70% of containerized imports from Asia by weight, according to the census data analyzed by Mr. Miller, with most of them routed through Los Angeles and Long Beach.

A series of developments chipped away at the West Coast’s dominance, including a widened Panama Canal in 2016 that made it easier for larger ships to get to different parts of the country and new tariffs on a range of Chinese goods imposed by the Trump administration. The rising tensions between Washington, D.C., and Beijing on trade caused American executives to begin shifting their production to countries outside China, meaning that East Coast ports made more sense as a point of entry.

The pandemic provided even more motivation for companies to push their shipping to the eastern half of the country. Backups developed at the big southern California ports beginning in 2020 as Americans stuck at home under Covid-19 restrictions ordered massive volumes of household goods; the queue of ships off the coast of California reached a high of 109 during January 2022. Then the U.S. began importing more goods from Europe, making an Atlantic Ocean crossing to various East Coast ports more critical.

One firm that began sending goods to the East Coast during this time was Abercrombie & Fitch, which also sells clothes under brands such as Hollister. The apparel chain used to move 90% of its goods through West Coast ports, mostly Los Angeles and Long Beach, where they were transferred to trucks and trains and hauled to a warehouse in New Albany, Ohio. From there the goods would be sent to two fulfillment centers and more than 500 stores across the country.

But surging volumes during the pandemic caused freight delays, adding weeks and sometimes months to deliveries. So the retailer, which had $2.6 billion in net sales in the U.S. in its most recent fiscal year, started to move all of its imports by truck. Because the West Coast was so congested, Abercrombie & Fitch started sending a larger share of goods to the Port of New York and New Jersey, roughly 500 miles from its Ohio warehouse.

Today the company ships 25% of its clothing through East Coast ports, primarily New York and New Jersey, said Larry Grischow, executive vice president of supply chain and procurement for Abercrombie & Fitch. Even after the company returns to the railroads, he expects to use the East Coast as a hub—especially as more of the company’s apparel production moves away from China to countries such as Indonesia and Bangladesh that can connect to the East Coast via routes that run through the Suez Canal.

“We are going to continue to operate in a way where we can flex from coast to coast,” he said.

Newell, the Atlanta-based company that makes Yankee Candles and Sharpie markers, is another company that decided to expand distribution networks in eastern states. It did so to save money, reduce risk and be closer to some of its customers.

This year, it added a new distribution center in Newville, Pa., which will mostly take goods from the Port of New York and New Jersey, and in 2023 it plans to open a distribution center in Gastonia, N.C., which will mostly take goods from Charleston and Savannah. It expects this will help it reduce transportation costs and the type of shipping delays that happened in the first years of the pandemic. It will keep two distribution centers in California and one each in Tennessee, Missouri and Ohio.

“The key is we don’t want to put all of our eggs in any one basket,” Chris Peterson, Newell’s president and chief financial officer, said during an interview on this subject in April.

The threat of a dockworkers strike this year added even more motivation for some companies to shift from the West Coast. Trane Technologies, which makes heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems for buildings and transportation, used to import more than half of its goods for North America through ports on that side of the country, mostly Los Angeles and Long Beach.

This year the Irish company is sending 70% of its products, such as heating and air units as well as service parts, via the East Coast mainly because of the labor talks. The majority will go through Savannah, with some also flowing through Charleston, Jacksonville, Fla., and Houston. Trane has annual revenue of more than $14 billion.

Tom France, Trane’s vice president of logistics, said he expects very little of the cargo will return to the West Coast even after the labor talks conclude with a new contract. He said he would rather use an ocean service that takes 10 days longer to reach an East Coast port but is consistent than a faster service to the West Coast that can be delayed by anywhere from two to 15 days.

With more unpredictability, he said, “you have to carry more inventory, do more contingency planning and you have a much bigger cost.”

In January Trane will begin shipping parts to customers from a new 175,000-square-foot distribution center in Atlanta that will complement a 400,000-square-foot distribution center that Trane opened there in 2019 to process residential equipment. Both facilities will be fed from the Port of Savannah, a four-hour drive away.

“Our business is basically where people are,” Mr. France said. “In the United States, most of the people, most of the buildings, most of the infrastructure, is east of the Mississippi.”

The operator of the Savannah port is taking several steps to prepare for more traffic. It is spending more than $1.3 billion over the next few years to double the number of berths that can unload from large container ships and expects next year to complete a 300,000-square-foot warehouse that will allow importers to quickly transfer cargo from ocean containers to truck trailers for distribution inland.

The warehouse will be operated by NFI, which stores and distributes goods for some of the country’s biggest retailers. NFI executives said the company is making $150 million in investments for similar facilities near ports at Houston and Norfolk, Va.

Griff Lynch, executive director of the Georgia Ports Authority, which runs Savannah’s port, said companies wouldn’t be investing in warehouses and distribution in the Savannah area in such a big way if it was a temporary solution.

“A lot of businesses are putting a flag in the ground here,” he said. “We have a massive opportunity to expand.”

Source: Hellenic Shipping News