The commodity market boom is over. Energy, metals and agriculture prices have all tumbled from their March peak on inflationary recession fears amid a slew of economic warning signs, but a commodity bust is far from inevitable.

Since early 2020, more and more analysts have been championing the idea of a new commodity supercycle, with an economic recovery turbo-charged by low interest and pandemic-led fiscal stimulus measures, and as investment into decarbonization projects accelerated to meet net-zero targets.

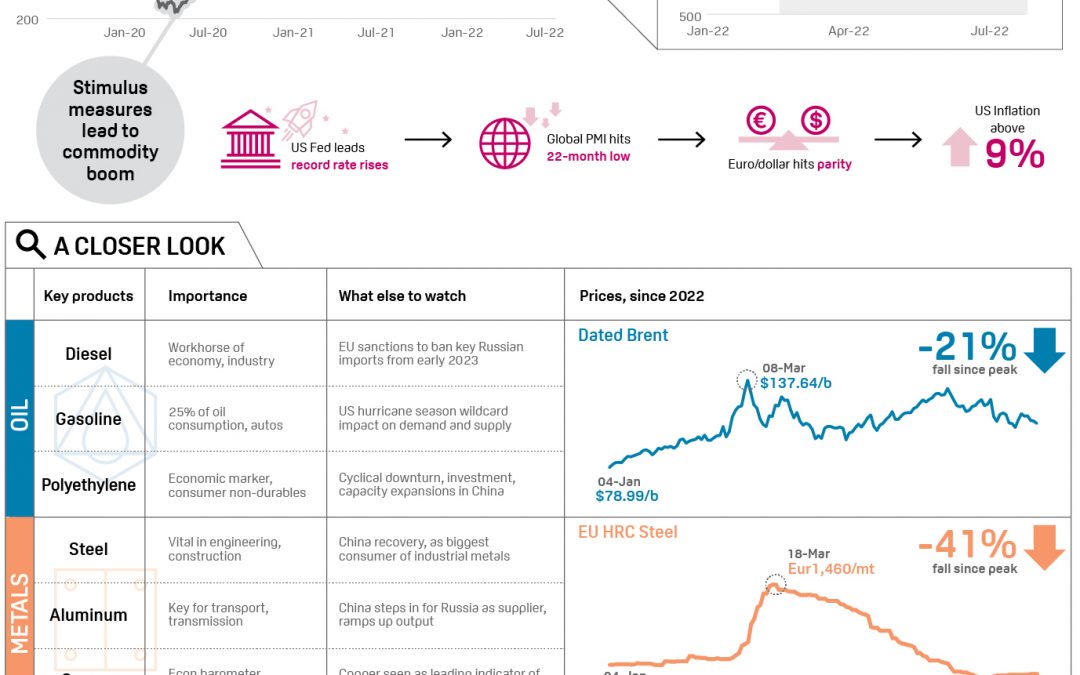

The S&P GSCI has almost quadrupled since early 2020 and this year has virtually doubled. But since June, the key commodity index has been on a downward trajectory, raising questions around the supercycle theory often described as a structural upward shift in commodity demand.

Key industrial metals such as steel, aluminum and copper have all led the collapse from their March peak. EU hot rolled coil steel is down more than 40% as assessed by S&P Global Platts.

Global manufacturing is creaking, with the July PMI data, a leading barometer of economic health, at its lowest in two years. The US Federal Reserve has raised interest rates by 75 basis points for the second month in a row in a bid to thwart runaway inflation at over 9% in June. And it’s a similar pattern of inflation risks and monetary tightening seen across Europe.

S&P Global Platts Analytics sees global GDP growth below 3% in 2022 and “the balance of risks is clearly on the downside with recession probabilities rising” amid “very concerning” inflation trends, after 2021’s booming GDP growth of 6%.

Oil and agriculture prices have also come off March highs, with the key Dated Brent crude benchmark and the Russian wheat price falling by close to 20%.

Energy and agriculture have not fallen at the same rate as metals given tighter supply balances, with Russia a crucial energy and crops supplier, amid uncertainties that these crucial commodities will continue to be exported at the same rate.

Russia stands alongside Saudi Arabia and the US as one of the three largest crude producers, makes up 40% of the EU’s gas needs, while Russia together with Ukraine supply a third of the world’s wheat.

“Industrial metals are pressured by China growth/demand worries while the product fuel market remains incredibly tight due to Russian sanctions … so industrial metals traders focus on demand while oil traders focus on supply,” said Ole Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo Bank. “The correlation will probably only reassert itself when China gets the virus under control.”

Commodity-consuming behemoth China’s subdued demand given its own pandemic-related difficulties may only last so long – and offset some of the weakness being seen elsewhere.

And on the supply side, EU’s sanctions on Russia’s oil imports kick in early next year, given China and India have been stepping in where European and US customers have already found alternative suppliers.

Own worst enemy

The key debate is how much high prices is leading to demand destruction amid fears of an inflationary recession and how much commodities are trading off their own fundamentals and still tight supply and demand balances.

If oil and wheat stay high despite the economic weakness, even more damage could be inflicted on the global economy and, ultimately, commodity demand, pointing to the urgency of OPEC+ to bring on extra barrels and the US to keep strategic petroleum reserves flowing.

Agriculture doesn’t have the same back-up plans, highlighting the risks around security of supply.

“The fact that prices remain elevated even as demand has slowed will lead to stagflation until demand falls further, creating a deeper recession versus what investors are expecting,” said Mark Rossano, CEO of C6 Capital Holdings.

Dated Brent remains in triple digits after peaking at close to $140/b in March and well above the $80/b at the start of 2022, while Russian wheat 12.5% FOB Black Sea is also still comfortably above levels seen at the start of the year.

Economics kick in

But while commodities trade off their own balances, it is clear economic warnings are translating to commodity price declines.

“Gasoline demand has proved a function of simple economics rather than being a price-resistant outrider of the commodities supercycle,” said Paul Horsnell, head of commodity research at Standard Chartered, which has regularly played down the supercycle theory.

But Jeff Currie, head of commodity research at Goldman Sachs, believes recessions are a natural part of a lengthy supercycle, given the reliance on key commodities that are hard to find replacements for. The ramping up of green initiatives will pull on demand for more commodities, plus the ongoing need to meet current food and energy security needs.

Ultimately, the journey has just begun, and while some parts of the world are in a downward spiral, there are still signs of growth.

“Growth and end-user demand is slowing, not contracting,” noted MUFG Bank. “This matters as commodities are spot assets, driven by demand levels, and, thus, the bullish commodities conviction holds as long as demand levels are still above supply levels.”

“We acknowledge that when the global economy is in recession for a protracted period, commodity demand, and with it prices, falls… though, we are not yet at this state,” the bank added.

Whether this is a deep cyclical downturn or a bumpy post-pandemic slump in the new supercycle may well depend on how the market and policy makers respond. Only one thing is clear: Both sets of protagonists are wondering if they are still playing catch-up.

Source: Hellenic Shipping News