In a small, rustic shipyard on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica, a small team is building what they say will be the world’s largest ocean-going clean cargo ship.

Ceiba is the first vessel built by Sail Cargo, a company trying to prove that zero-carbon shipping is possible, and commercially viable. Made largely of timber, Ceiba combines both very old and very new technology: sailing masts stand alongside solar panels, a uniquely designed electric engine and batteries. Once on the water, she will be capable of crossing oceans entirely without the use of fossil fuels.

“The thing that sets Ceiba apart is the fact that she’ll have one of the largest marine electric engines of her kind in the world,” Danielle Doggett, managing director and cofounder of Sail Cargo, tells me as we shelter from the hot sun below her treehouse office at the shipyard. The system also has the means to capture energy from underwater propellers as well as solar power, so electricity will be available for the engine when needed. “Really, the only restrictions on how long she can stay at sea is water and food on board for the crew.”

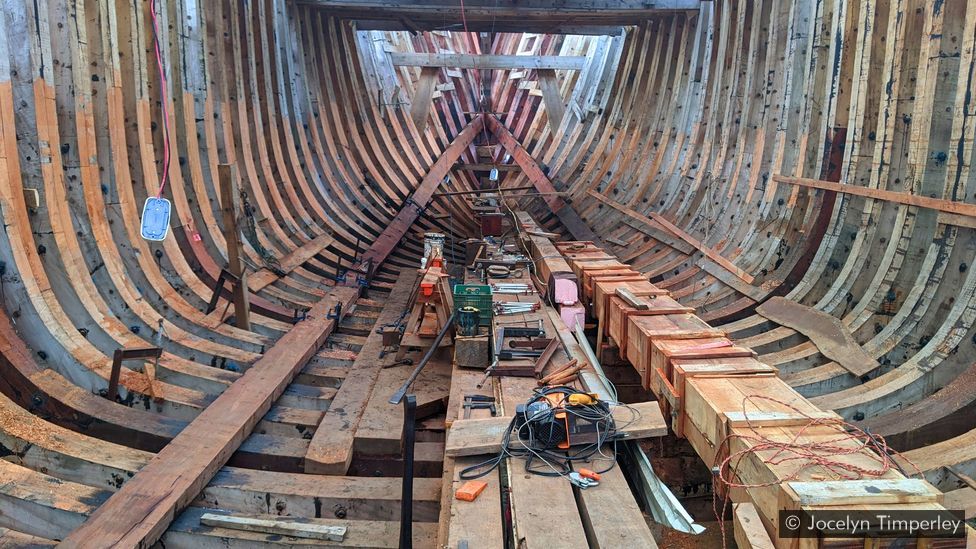

Right now, Ceiba looks somewhat like the ribcage of a gigantic whale. When I visit the shipyard in late October 2020, armed with the usual facemask, alcohol gel and social distancing practices, construction has been going on for nearly two years. The team is installing Ceiba’s first stern half frame – a complicated manoeuvre to complete without the use of cranes or other equipment. Despite some hold-ups due to the global pandemic, the team hopes to get her on the water by the end of 2021 and operating by 2022, when she will begin transporting cargo between Costa Rica and Canada.

With the hull and sail design based on a trading schooner built in the Åland Islands, Finland, in 1906, from the horizon Ceiba will have the appearance of a classic turn-of-the-century vessel, when the last commercial sail-powered ships were made. “They represented the peak of working sail technology, before fossil fuel came in and cut them off at the ankles,” says Doggett. Sail Cargo also plans to explore the use of more modern sail technology, she adds, such as that used in yachts, in its future boats.

For her builders, one of the ship’s main attractions is to provide a much-needed burst of (clean) energy in an industry long dragging its heels on climate. The global shipping sector emitted just over a billion tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2018, equivalent to around 3% of global emissions – a level that exceeds the climate impact of Germany’s entire economy.

In 2018, countries at the UN shipping body the International Maritime Organization (IMO) agreed on a goal to halve emissions in the sector by 2050, compared with 2008 levels. Climate advocates welcomed this as a step forward, even if the goal was not as ambitious as needed to align with the Paris Agreement target of limiting temperature rise to “well below 2C”, let alone the efforts to limit it to 1.5C. But despite the climate goal and some efficiency gains over the past decades, the sector continues to be slow to implement concrete, short-term measures to cut emissions. A major study found shipping emissions rose by 10% between 2012 and 2018, and projected that they could rise up to 50% further still by 2050 as more and more things are shipped around the world. Most recently, the IMO approved new efficiency measures which will be voluntary till 2030, which critics say will allow the industry’s emissions to keep rising over the next decade.

Others have more ambitious goals. “There’s actually loads of really great innovations happening that could transform [shipping emissions],” says Lucy Gilliam, shipping campaigner at non-profit Transport and Environment. “It’s not that we don’t have great ideas. The problem that we have is that fossil fuels are still too damn cheap. And we don’t have the rules to force people to take up the new technology. We need caps on emissions and polluter pays schemes so that the clean technologies can outcompete fossil fuels.”

Doggett agrees that far more policy and government action is needed to help reduce shipping emissions, and part of Sail Cargo’s remit is pushing for this. At the same time, she says, the private sector can demonstrate what is possible.

“I feel like the largest barrier to success is proving that [clean shipping] is valuable,” she says. “I’m really hoping that if we can set a precedent with a for-profit company that can claim the world’s largest and completely emission free [cargo ship], then we can wave these numbers like a flag and say, look, people who are writing the policy, we already did it today. Because it’s not impossible. And I don’t understand, frankly, why it hasn’t moved faster.”

Ceiba is small for a cargo ship – tiny in fact. She will carry around nine standard shipping containers. The largest conventional container ships today carry more than 20,000 containers.

She is also relatively slow. Large container ships typically travel at between 16 and 22 knots (18-25 mph/30-41 kph), according to Gilliam. Ceiba is expected to be able to reach 16 knots at her fastest, says Doggett, and easily attain 12 knots, although the team has conservatively estimated an average of 4 knots for trips until they can test her on the water. She will likely be significantly faster than existing smaller sail cargo ships that don’t have the added benefit of an electric engine.

But Doggett is emphatic that the company is not trying to directly compete with mainstream container ships. “In many ways it’s a completely different service offering,” she says. “But at the same time, we’re trying to prove the value of what we’re doing, so that we can inspire those other large for-profit companies to pick up their game.”

And while Ceiba is small compared to most container ships, she is still around 10 times larger than the most established fossil-free sailing cargo vessel currently in service, the Tres Hombres. Sail Cargo hopes this means she can help bridge the gap between these smaller ships and even larger emissions-free ships in the future. Sail Cargo is already planning a second similar vessel, and is also in the initial stages of plans to build a much larger, more modern design. “In five years, we would hopefully be laying the keel of a very large, commercially viable competitive vessel,” says Doggett.

Before even leaving the shipyard, Ceiba’s diary is filling up fast. With at least a year to go until she is on the water, she already has a surplus of interest for her initial northbound voyages from companies willing to pay a premium for emissions-free transport of products such as green coffee, cacao, organic cotton and turmeric oil. Bio-packaging, electric bicycles and premium barley and hops for Costa Rica’s burgeoning craft-beer market are among bookings so far on the southbound journeys.

But, being a world-first, there are some aspects of Ceiba’s design that have yet to be proven at sea – including her specific combination of wind power and an electric engine. Ceiba has a regenerative engine: when she is travelling using her sails, her propellers can be used as underwater turbines to capture excess energy, similar to how regeneration mode in an electric car can capture excess kinetic energy when you brake. The electricity, along with that generated by the solar panels, can then be stored in the battery until it is needed to drive the ship. Importantly, and unlike many other ships that already use some kind of electrical engine, Ceiba’s engine is purely electric and does not have diesel as a back-up option. She is genuinely fossil free.

“Having a real-life, albeit small, working model of hybrid-electric sail is super useful, and hopefully replicable and scalable,” says Gilliam. “It’s not just sailing vessels like Ceiba; we could have much larger commercial ships with sail power.”

For example, sail technologies could help to extend the range of other greener technologies currently being considered for far bigger ships, such as hydrogen fuel cells

Indeed, some commercial cargo ships are already fitting rotor sails and rigid-wing technology for an added boost. And, notably, a further fuel-efficiency measure for conventional ships is to reduce their speed – which in turn makes slower ships like Ceiba more competitive.

But for Gilliam, the greatest value in a project like Sail Cargo is its ability raise awareness about shipping emissions and the lifestyle changes which are needed alongside technology to tackle them. “It offers an alternative vision of ways of living. It’s inspiring for young people,” she says.

Walking around the shipyard I meet Julian Southcott, a shipwright timber framer from Australia. He’s measuring and cutting wood, with a diagram of the ship’s structure lying nearby. “It’s like a big puzzle,” he says. Southcott came out to join the team building Ceiba last year, attracted to the project because it is “actually trying to make a difference to the planet and what’s going on in the world”, he tells me. “It’s kind of hard to find work that you’re ethically aligned with, in this day and age,” he says. “I guess once she’s in water, it’s going to touch a lot of people.”

And Sail Cargo also has a wider vision than just building ships, no matter how green. “We like to say we’re a shipyard for coastal communities,” says Doggett. “So what we want to do here is establish a really beautiful little scenario where we can be training people, hopefully paying them and offering free courses, providing them with life skills that they ask for, and that are relevant, and can give them maybe a source of income, because there’s almost no industry here.”

I talk with Jamilet Espino Castillo, a young woman from the local Punta Morales area who began working at the shipyard as a cleaner around a year ago. After seeing the shipyard’s carpenters at work, she was inspired to switch jobs, and has now been working with them in carpentry for six months. “It looked really exciting,” she says. “I love it.”

There are other ways the shipyard is unusual. It has both a tree planting programme and an onsite vegetable garden, and the latter is where I meet Mariel Romero Mendez, the Costa Rican coordinator of AstilleroVerde (literally “Green Shipyard”), the non-profit arm of Sail Cargo.

The garden, run on organic principles, provides food to the workers at present, but the plan is to scale it up. “The idea is to start with us and then expand to help [with food security] around town,” says Romero Mendez. She wants to set up an agroecological school to collect and disseminate knowledge among the local community. “To young people, more than anything, who are more distanced from agriculture,” she says.

The kitchen itself, which provides all meals for the 30 or so workers, is run by two local, self-managed women’s associations. Shifts rotate based on who need the most financial assistance that week. Sail Cargo has also worked hard to restore greenery to the shipyard, which was more or less a barren field when they first rented it, according to Doggett.

In addition to its food projects, AstilleroVerde also has an education centre, which has offered locals boat-building and blacksmithing courses, although these have now been put on pause due to the pandemic.

Sail Cargo has pledged that 10% of its profits will go to back to the planet, including donations to AstilleroVerde as well as other charities. In addition to this pledge, it aims to ensure Ceiba is “carbon negative” by planting 12,000 trees in Costa Rica before she is launched, giving each four years of care after planting. One in every 10 of those trees will be destined for building future ships, while the rest will overcompensate for the wood used to build Ceiba.

So far, 4,000 trees have been planted on private land in the Monteverde region of Costa Rica, and ensuring the tree planting occurs in a holistic fashion with the shipbuilding. “We are physically cutting down trees in our community, we are using them in a wood ship that is for the environment, and we are planting those trees back in our community,” says Doggett.

Most of these trees are native species, which are slow to mature. It takes about 50 years to grow the trees from which Ceiba is built to maturity. But Doggett is playing the long game; barring unforeseen circumstances Ceiba will be seaworthy until she is 100.

Sail Cargo’s focus on a holistic, truly circular system of shipbuilding may be praiseworthy, but for now it really is just a drop in the ocean. As pressure builds on the shipping industry to act on climate change however, projects like this could both offer an alternative to conventional shipping and help to influence the mainstream industry.

After a day spent at the shipyard watching Ceiba being built, I ask Lynx Guimond, another co-founder of Sail Cargo, what he thinks is really needed to cut the shipping industry’s sizeable emissions. Perhaps surprisingly for someone in the middle of building a ship, he tells me that one of the solutions is simply less shipping. “At the end of the day we just need to transport less stuff.”

Source: Hellenic Shipping